Refugees Then and Now

Haiti captured headlines in 2021 because of three crises: the assassination of the country’s president in July, followed by a major earthquake in August, and then an exodus in autumn of Haitians who went first to Mexico and then tried to cross into the United States at the border with Texas.

This was not the first time, though, that so many Haitians sought asylum in the United States. Thousands who fled from the island in the 1990s were refused entry to this country, many of whom were incarcerated at the U.S. base at Guantanamo Bay. In the 1980s the Reagan administration had been equally unwelcoming: more than 400 boats of migrants were intercepted by the U.S. Coast Guard and returned to Port-au-Prince, Haiti’s largest city.

What is it about Haiti that has impelled people, decade after decade, to leave their country? To answer that question it will help to go back in time to the uprising of enslaved people over two centuries ago.

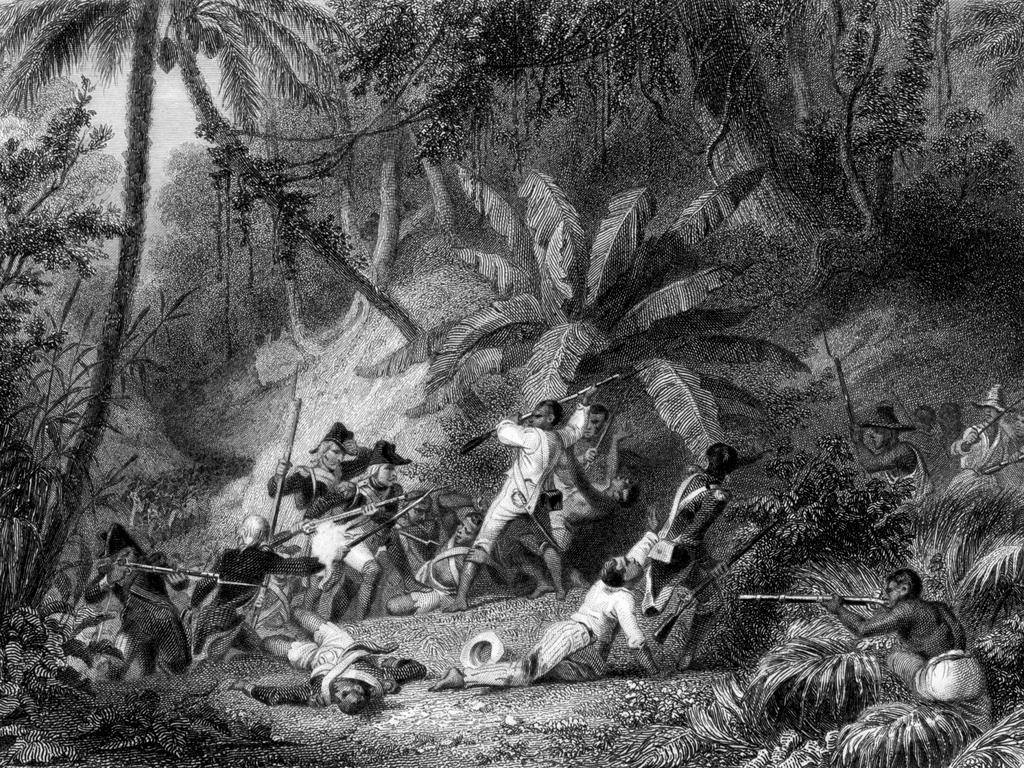

Although the Haitian Revolution succeeded in giving birth to a new republic in 1804, many of those living on the island — whites understandably but also people of color — fled the country because of the violence and devastation. The 13-year war of liberation not only took hundreds of thousands of lives but also made much of the island uninhabitable. Plantation fields and buildings were destroyed by fire. Port-au-Prince and Cap Francais, the two largest cities on the island, were reduced to ashes. Plantation households, joined by whites and people of color living in ravaged communities, sought desperately to get away, scrambling to pack up belongings and board vessels in the harbors of the island.

Burning of the town of Cap-Francais in 1793. Ships holding escaping colonial refugees desperately await permission to depart. Cap Francais was for years a battleground where rebel and French forces fought to control the streets and the port, with enormous loss of life on both sides.

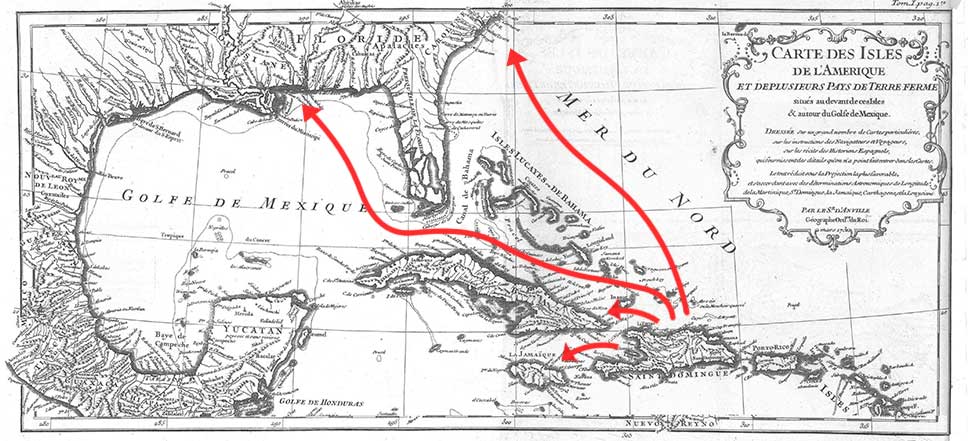

Many of those fleeing the island ended up in nearby Jamaica and Cuba, while others sought a new life in the United States. Thousands of refugees arrived at ports in Virginia, South Carolina, and Maryland. In the year of 1810 alone, about 10,000 refugees landed in New Orleans, where they doubled the population.

During and following the Haitian Revolution, most of the refugees from the island went to Cuba, Jamaica, Louisiana, or the Northatlantic states of the U.S.

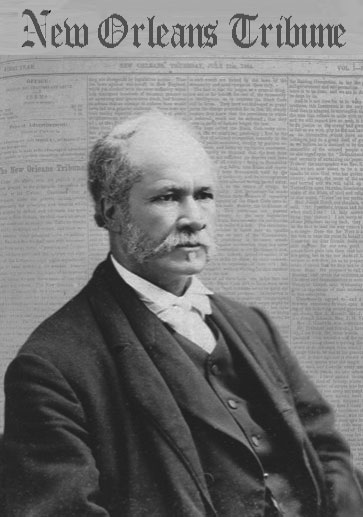

Many refugees from Haiti supported the abolition of slavery in this country. Dr. Louis Roudanez, physician and journalist, was the son of racially mixed Haitian refugees who came to New Orleans after the revolution. Giving a voice in the South to the abolitionist cause during the Civil War and Reconstruction, he was a founder of two Black newspapers.

Refugee immigration was only one consequence of the Haitian Revolution for the United States. Another was the Louisiana Purchase. The defeat of French troops in Haiti, which had been France’s most profitable colony, led Napoleon and his advisors to re-evaluate the benefits and costs of holding on to French-claimed land in North American. The French sale of the Louisiana Territory to the United States in 1803 nearly doubled the size of the country.

As well, the success of the Haitian revolution demonstrated to North American enslaved people and their owners alike that the system of slavery was vulnerable — it could be overthrown. Those opposed to slavery in this country were given hope by the Haitian example.

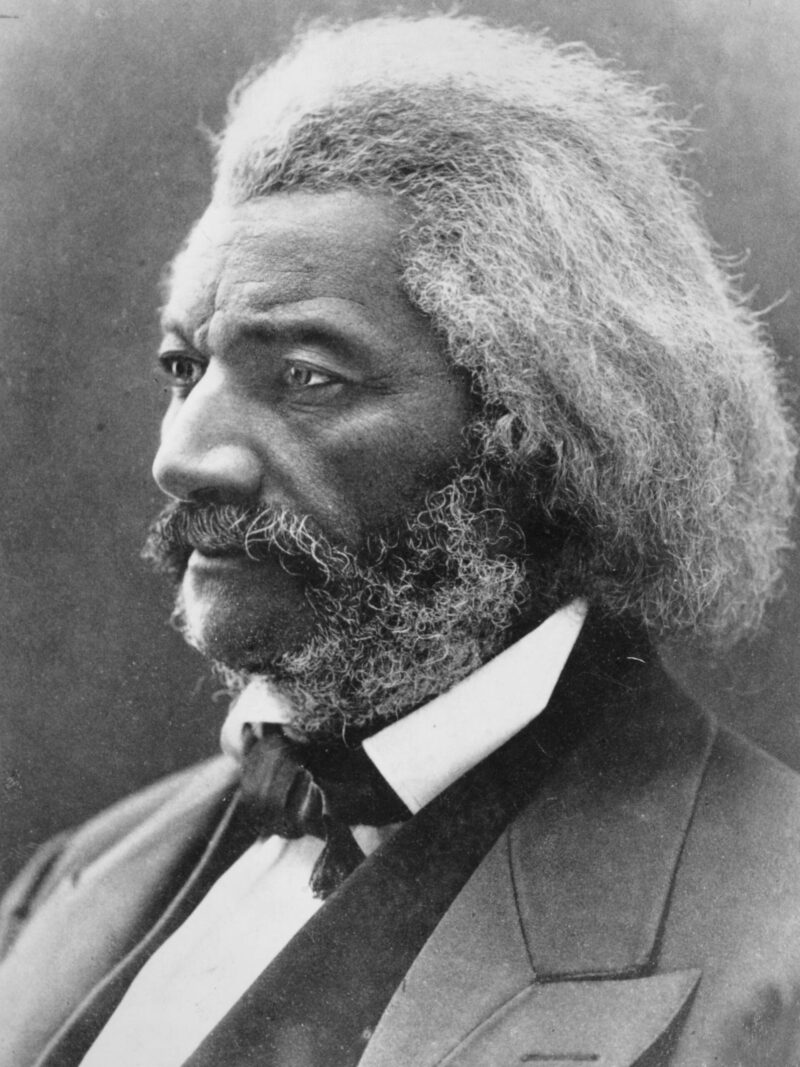

Frederick Douglass, a former enslaved person who became a leader of the abolitionist movement, said this in a speech in 1893:

“We should not forget that the freedom you and I enjoy to-day … the freedom that has come to the colored race the world over, is largely due to the brave stand taken by the black sons, of Haiti ninety years ago….. Their swords were not drawn and could not be drawn simply for themselves alone. They were linked and interlinked with their race, and striking for their freedom, they struck for the freedom of every black man in the world.”

William Douglass, a writer, abolitionist, and publisher of the North Star newspaper, spent the years 1889 to 1891 in Haiti as U.S. ambassador to the country.

Douglass commented in a speech given at the World Fair in 1893: “Haiti is black, and we have not yet forgiven Haiti for being black.… After Haiti had shaken off the fetters of bondage, and long after her freedom and independence had been recognized by all other civilized nations, we continued to refuse to acknowledge the fact….and treated her as outside the sisterhood of nations.”

Although the Haitian Revolution inspired anti-racial movements worldwide, the new republic did not live up to its promise. In addition to having to deal with the devastation that had occurred during the years of revolutionary upheaval, there was another problem that the republic faced: how to respond to on-going intimidation from abroad. It’s true that French troops had been decisively defeated in the mountains, fields, and townships of Haiti. Yet France was not about to give up its control of the island. For decades following the revolutionary war, the rulers of France continued to threaten to reconquer Haiti militarily and restore colonial rule and slavery. In 1824, King Charles X repudiated envoys that Haitian President Boyer sent to Paris to negotiate for a peaceful parting of the ways that included French recognition of Haiti’s independence as a nation.

As a condition of that independence, the king of France decreed that Haiti would have to pay 150 million francs within five years to compensate for slave owners’ lost revenue. We see below the French envoy sent by Charles X delivering the demand to Haiti’s President Boyer. To compel Haitian acceptance, this mission to the island was accompanied by 14 warships bearing more than 500 cannons.

Marlene Daut, Professor of African Diaspora Studies, at the University of Virginia, writes, “Rejection of the ordinance almost certainly meant war. This was not diplomacy. It was extortion.”

Boyer signed the document, although the amount of money France demanded just in the first installment – 50 million francs — was far more than Haiti could afford to pay. The Ordinance stated that if Haiti could not come up with this amount, it would have to borrow from a French bank. And that’s what happened; Haiti was cast deeply into debt like so many other colonized countries that have fought for and won nominal independence. Going forward from that point in time, Haiti was impoverished and unable to shape its own economic future.

Accompanying Haiti’s wrecked economy was the failure of the revolution to establish a democratic society based on human rights or social justice. The first post-revolutionary leader of the country was General Jean-Jacque Dessalines who declared himself “Emperor.” He was murdered in 1806 during a revolt by his former supporters. Following his death, two other military leaders, Alexandre Pétion and Henry Christophe, divided Haiti between themselves.

For the following two centuries and still today, Haiti’s political leadership, abetted by France, other European powers and the United States, has supported a wealthy few while impoverishing and disempowering everyone else. Racism has played a role in U.S. foreign policy toward Haiti ever since George Washington and Thomas Jefferson approved of financial assistance to help the island’s white plantation owners put down the slave rebellion. Frederick Douglass commented in a speech given at the World Fair in 1893: “Haiti is black, and we have not yet forgiven Haiti for being black.… After Haiti had shaken off the fetters of bondage, and long after her freedom and independence had been recognized by all other civilized nations, we continued to refuse to acknowledge the fact….and treated her as outside the sisterhood of nations.”

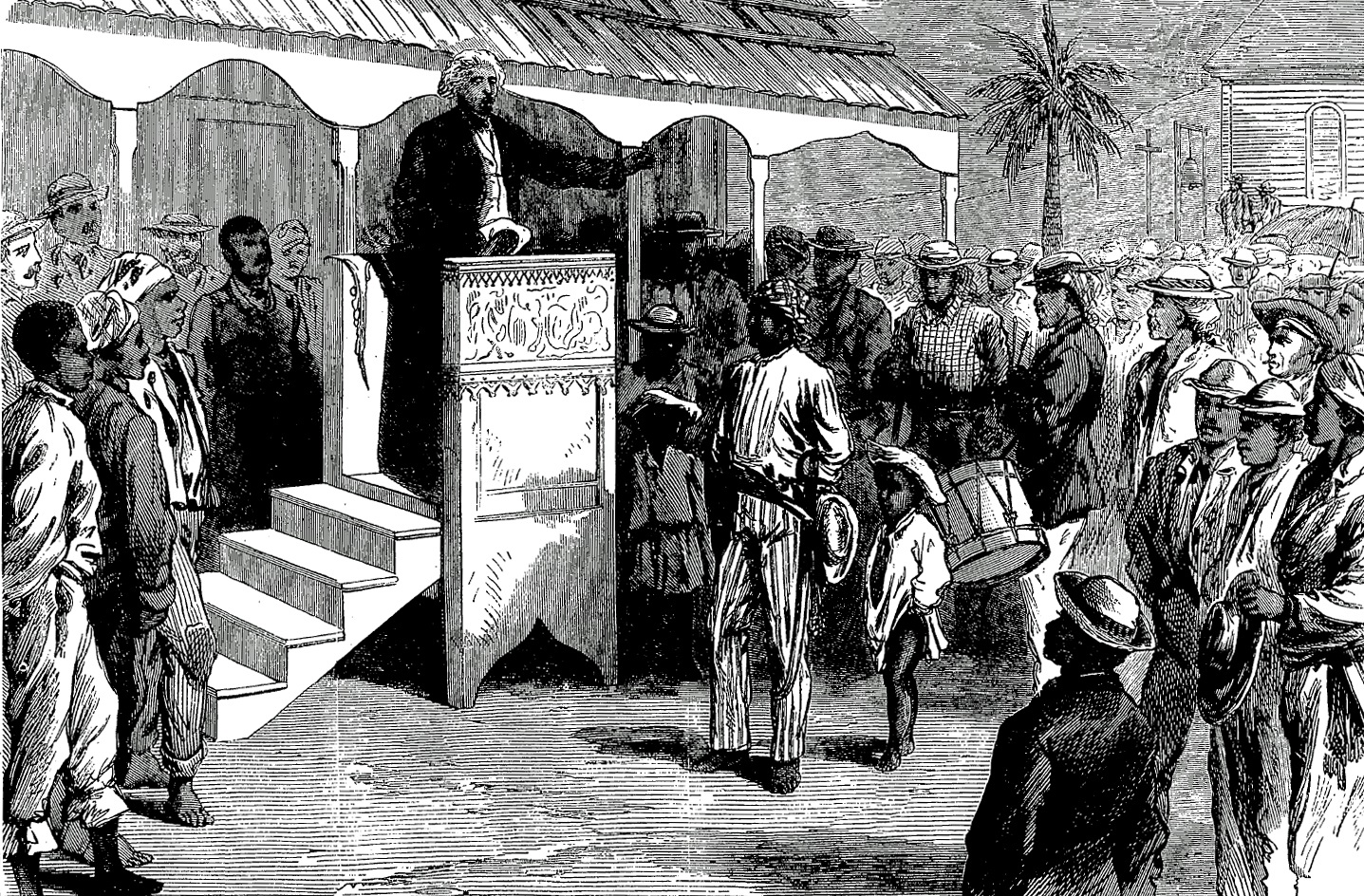

Frederick Douglass speaking at the Haiti Pavilion of the 1893 World Fair in Chicago.

In the 20th century, from 1915 to 1934, Haiti was occupied by the U.S. army, without doing anything to undo the prevailing economic and political causes of poverty and corruption. With the backing of the United States a single family (headed by Francois Duvalier and then his son Jean-Claude) ruled Haiti from 1957 to 1986. They enriched themselves while their personal paramilitary force, the dreaded Tonton Macoute, routinely kidnapped and tortured their so-called “enemies.” Tens of thousands of Haitians were murdered by the regime, which relied on weapons trafficked from the United States. Remaining deadly and destabilizing in Haiti today is the import of firearms and ammunition from Haiti’s northern neighbor. These enable the police and gang violence that terrorizes Haiti’s neighborhoods in Port-au-Prince and other cities.

Hundreds of Haitians take shelter in a sports stadium, getting away from gang violence in their neighborhoods

Haiti’s history illustrates the hazards of the transition from colonial domination to independence: the colonial occupiers are successfully expelled, but retain an influence that stands in the way of a new nation’s self-determination. During the 19th and 20th centuries, the sovereignty achieved by many of the world’s colonized countries, Haiti included, represented only a first step forward. Foreign powers found many ways of continuing to exert control, ranging from economic domination by multinational corporations to the supply of weapons that allows ruling elites in those countries to violently suppress their political opponents.

The result has been that in Haiti – as in similarly impoverished countries worldwide – hardship and fear motivate people to to flee their home country. More effective and humane than a U.S. policy that repels refugees at the border would be an approach that recognizes and addresses the root economic, political, and climate causes of emigration.

Additional Reading:

Felipe Filomeno, “Who is responsible for migrants?”

Laurent Dubois, Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution

Laurent Dubois, Haiti. Information about Haitian history is also available on other pages of this website.

If you would like assistance in getting reading access to any of the publications listed above, contact us here.

Video:

PBS, The Haitian Revolution

Vox, Divided island: How Haiti and the Dominican Republic Became Two Worlds

PBS, Haiti and the Dominican Republic: An Island Divided

117 guns, 116 boxes of ammunitions, 30,000 cartridges, 15 handcuffs, military uniforms and boots smuggled from Miami into Haiti in September, 2016.