Punishment: From 1619 Until Now

The 1619 Project is an exploration of United States history that looks at the roles that Black Americans have played in building this country, with emphasis on the legacy of slavery. That legacy continues today to influence the nation’s economic, political and cultural institutions, including its system of criminal justice.

The ideals of freedom and democracy upon which our nation was founded are honorable and deserve our support, but often they have gone unfulfilled. How can we live up to these high-minded values today?

Ferguson Prison Farm, Texas in 1968 (photo by Danny Lyon)

The United States has the highest rate of incarceration in the world. This nation has about five per cent of the human population on the planet, but holds nearly one quarter of the world’s prisoners.

One in five Americans has a criminal record. Seven million people are under supervision by the penal system. One in three black men will be imprisoned during his lifetime. How did this come about?

America’s system of mass incarceration has a long history. Some of its principles and practices– the ways in which it treats people of color and white people too — can be traced back to methods of discipline and punishment that were used on people who were enslaved and brought from Africa to the “New World.”

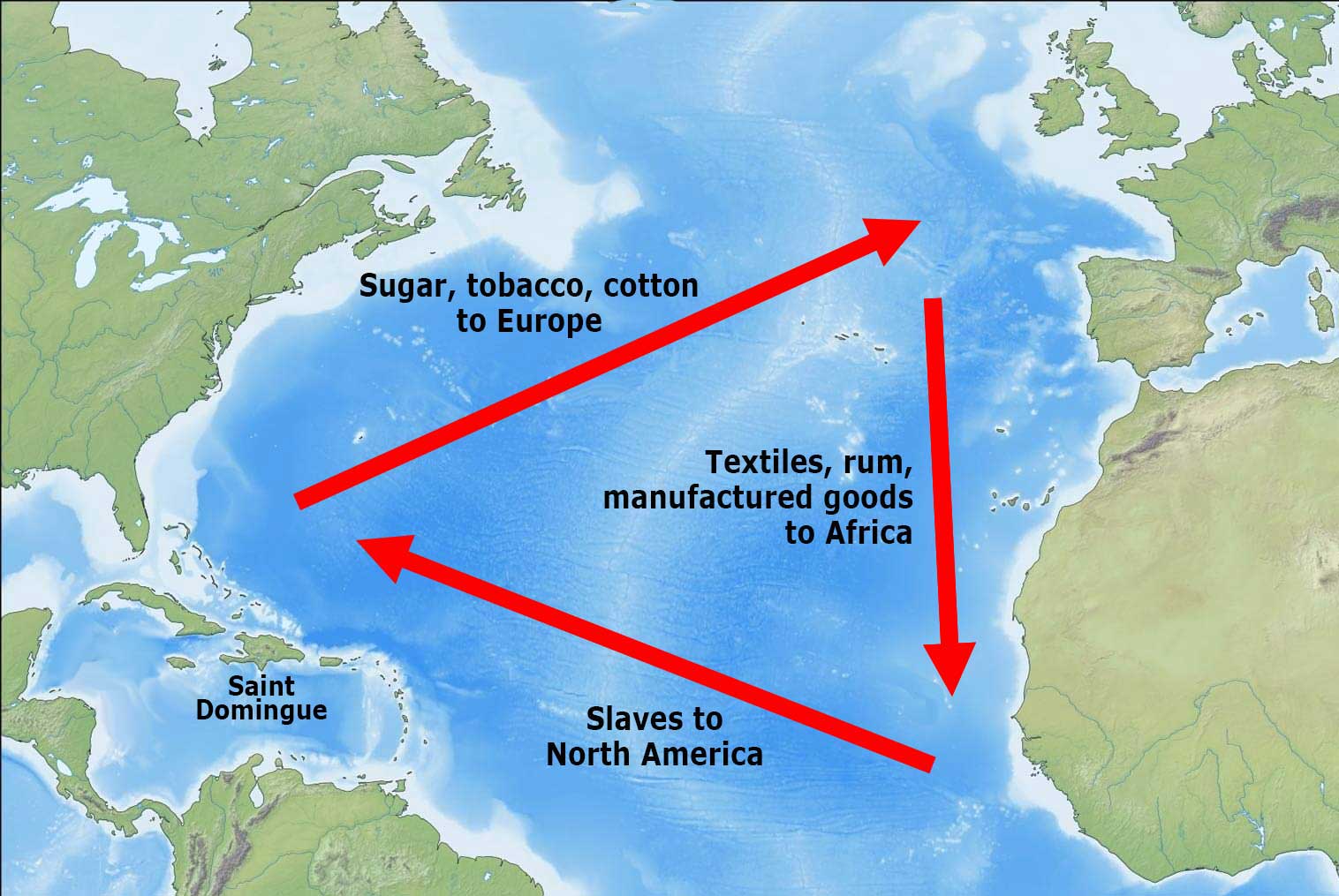

The North Atlantic slave trade conducted by the thirteen colonies actually began in the 1500s in the Caribbean. One of the islands there was called “Saint Domingue” (known today as “Haiti”) by its French colonial settlers, who imported several million Africans and forced them to labor on the island’s plantations. Henry Louis Gates points out that Saint Domingue “is the birthplace of the black experience of the Americas.”

Through the labor of enslaved people, Saint Domingue became during 18th century the most profitable colony in the world, supplying about one half of the sugar and coffee consumed worldwide. And commercial interests in the United States as well as France benefited from partnering with the island’s plantation owners. With an economic stake in protecting trading relationships, the “Founding Fathers” joined with France in seeking to defeat the Black uprising on the island that began in 1791.

The Founders offered what they took to be a moral justification for an economy based on slavery — a justification that was based on racial difference: innate qualities were attributed to Black people that allegedly made them appropriate servants of their white owners. When these people rebelled, the white master class was not sympathetic. Responding to the slave uprising in Haiti, George Washington found it “Lamentable … to see such a spirit of revolt among the Blacks. Where it will stop, is difficult to say.” In a letter written to President John Adams in 1799, Secretary of State Timothy Pickering wrote, “Our Southern States … are yet in much danger from attempts to excite the blacks to insurrection.” It is essential, Pickering urged, “to guard against the danger to be apprehended from St. Domingo.”

In the 19th and 20th centuries, the idea of the innate inferiority of Black people shaped U.S. policy toward Haiti. In 1915 President Woodrow Wilson’s Secretary of State judged that sending U.S. Marines to occupy Haiti was necessary because Haitians have an “inherent tendency to revert to savagery.”

The nearly two-decade occupation of Haiti by U.S. armed forces (1915-1934) did nothing to counter the economic and political causes of poverty and corruption in the country. Haitian land was sold to U.S. companies, making life all the more difficult for farmers. Infrastructure improvements served mainly the wealthy. Some U.S. military leaders came to regret their role. “I spent thirty-three years and four months in active military service as a member of this country’s most agile military force, the Marine Corps,” said Smedley Butler, a former general in the U.S. Marine Corps. “During that period, I spent most of my time being a high class muscle-man for Big Business, for Wall Street and for the Bankers.”

Enslaved Africans arrive in Jamestown, Virginia in 1619.

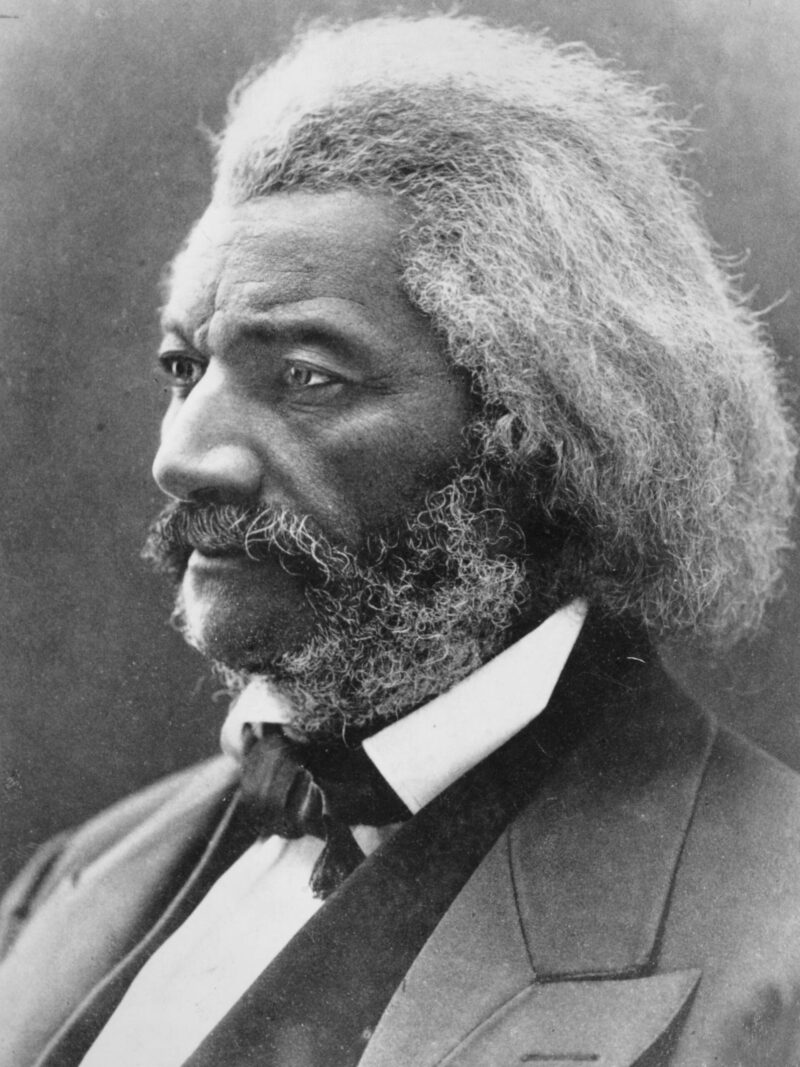

Frederick Douglass was an enslaved person who escaped to freedom and became a writer, publisher and leader of the abolitionist movement. He spent the years 1889 to 1891 in Haiti as U.S. ambassador to the country. In a speech given at the World Fair in 1893, Douglass commented: “Haiti is black, and we have not yet forgiven Haiti for being black.… After Haiti had shaken off the fetters of bondage, and long after her freedom and independence had been recognized by all other civilized nations, we continued to refuse to acknowledge the fact….and treated her as outside the sisterhood of nations.”

Frederick Douglass was an enslaved person who escaped to freedom and became a writer, publisher and leader of the abolitionist movement. He spent the years 1889 to 1891 in Haiti as U.S. ambassador to the country. In a speech given at the World Fair in 1893, Douglass commented: “Haiti is black, and we have not yet forgiven Haiti for being black.… After Haiti had shaken off the fetters of bondage, and long after her freedom and independence had been recognized by all other civilized nations, we continued to refuse to acknowledge the fact….and treated her as outside the sisterhood of nations.”

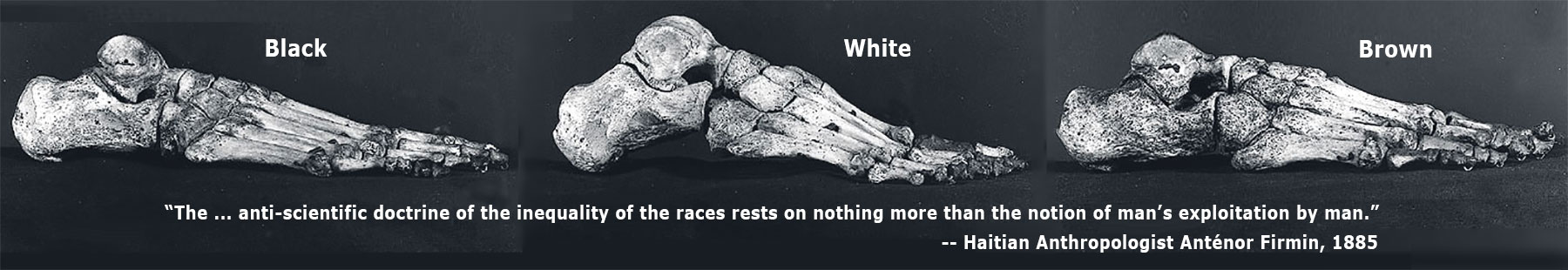

Racism has always been based on the idea that some people are by nature different from and superior to other people, which presumably gives those who belong to the first group the right to rule over those in the second group.

The particular difference that racism relies upon is skin color; the European and later the North American justification for slavery was that white people are by their very nature endowed with elevating qualities – reason, intelligence, self-control, or simply whiteness itself – that authorize them to own and direct the lives of people of color.

This rationalization for racism and slavery is empty: evidence from such diverse fields as biology, economics, sociology, and political science does not support it. The American Society of Human Genetics stated in 2018 that “Genetics demonstrates that humans cannot be divided into biologically distinct subcategories…. This is validated by many decades of research …. It follows that there can be no genetics-based support for claiming one group as superior to another.” Illuminating on this subject is Angela Saini’s book, Superior: The Return of Race Science.

Disagreement about Human Nature

“Man is born free, but everywhere is in chains.” – Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778), philosopher of the French Enlightenment and opponent of slavery

“Man is born free, but everywhere is in chains.” – Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778), philosopher of the French Enlightenment and opponent of slavery

A contemporary reading of Rousseau: Irrespective of their origins, humans have an enormous potential – and even a longing – to learn and create, to respect and care deeply about one another. But the environments in which they grow up and live may suppress this potential, leading people to become indifferent or even enemies. Racism develops out of that, and is a consequence of domination and miseducation, not of unchangeable human nature. We can do better.

Learn more about Anténor Firmin here.

Women Advocate for the Abolition of Slavery

In the 19th century many women who sought equality with men and advocated for feminist causes, the right to vote included, also joined the movement to abolish slavery. They argued that the common humanity of all people ethically rules out every kind of domination, whether based on color, gender, or any other such classification. Those enslaved, they argued, had to be recognized and treated as people, not as property

Frederick Douglass commented on women’s participation in the abolutionist movement, “When the true history of the antislavery cause shall be written, women will occupy a large space in its pages; for the cause of the slave has been peculiarly woman’s cause. “

Douglass held that women, no less than people of color, are fully capable beings: “Nature has given woman the same powers, and subjected her to the same earth, breathes the same air, subsists on the same food, physical, moral, mental and spiritual. She has, therefore, an equal right with man, in all efforts to obtain and maintain a perfect existence.”

“Mortals are equal, it is not birth, but virtue alone that makes the difference.” (French Society of the Friends of Blacks, 1794)

Maria Stewart, African American journalist, teacher, abolitionist, and women’s rights activist: “Give the man of color an equal opportunity with the white, from the cradle to manhood, and from manhood to the grave, and you would discover the dignified statesman, the man of science, and the philosopher.”

Lucretia Mott, American Quaker, abolitionist, women’s rights activist, and social reformer: “I have no idea of submitting tamely to injustice inflicted either on me or on the slave. I will oppose it with all the moral powers with which I am endowed. I am no advocate of passivity.”

Reconstruction After the Civil War

At the end of the Civil War (1861-1865), slavery was made illegal in the United States by ratification of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution. But “Reconstruction,” the turbulent era that lasted from 1865 until 1877, failed to deliver the human rights that emancipation had promised. There was a loophole in the 13th Amendment that helped Southerners keep Black Americans in bondage: the amendment prohibited slavery and servitude in all circumstances “except as a punishment for crime.” Southern states like South Carolina and Mississippi enacted laws that criminalized ordinary human activities — police were empowered to arrest Black Americans for “loitering” or “vagrancy,” for example. Convicted often of just such “crimes,” Blacks were imprisoned in large numbers and, in effect, returned to servitude.

As Bryan Stevenson, founder of the Equal Justice Initiative and law professor at New York University, points out, “After emancipation, black people, once seen as less than fully human ‘slaves,’ were seen as less than fully human ‘criminals.’ … Laws governing slavery were replaced with Black Codes governing free black people — making the criminal-justice system central to new strategies of racial control.”

The Civil War and Reconstruction left millions of African Americans penniless and landless. Lack of opportunity — and worse — came in many forms: terror at the hands of the Klu Klux Klan, having what little land you owned be poisoned and burned, punitive government policies that included denial of loans for your farm and withholding of aid after natural disasters. Some Blacks who tilled parcels of land had their property taken away from them when real estate interests, backed up by police and military enforcement, consolidated land holdings and restored them to white control, which was exercised no longer by the threat of violence on a slave plantation but now by a more rigorous system of incarceration.

Although some African Americans in the South did find employment as wage-earners, following the Civil War, the conditions of their labor were often scarcely more humane than slavery. Six million Black people migrated to the North between 1916 to 1970, seeking employment wherever they could find it.

Chained convicts built railroads in the South

Juvenile convicts at work in the fields, 1903

In the 1890s Southern states enacted “Jim Crow” laws that made it illegal for blacks and whites to share public facilities. Blacks had to use separate schools, hospitals, restaurants, hotels, bathrooms, and drinking fountains.

African Americans from Florida on their way to pick potatoes in New Jersey in 1940

We are currently living with the legacy of Reconstruction and the subsequent decades of discrimination and segregation. The typical white family has 8 times the wealth of the average Black family and 5 times the wealth of the typical Hispanic family, and the poverty rate for Black people (18.8 percent) is more than double that of whites (7.3 percent).

The crime rate, along with the unemployment rate, is higher in poor black neighborhoods, just as it is in poor white neighborhoods. Violent crime is related as well to urban pollution and decay, inequality, poor schools, absence of government services or assistance, family instability, drug addiction, housing foreclosures and evictions, and homelessness.

Today we have yet to put the legacy of slavery behind us, says Bryan Stevenson, “Hundreds of years after the arrival of enslaved Africans, a presumption of danger and criminality still follows black people everywhere.”

What is to be done? We know that alternatives exist. Countries like Norway and Austria have built criminal justice systems that protect communities more effectively and humanely than our system does. They are based on policies of rehabilitation, not retaliation. Social policy in these countries is also successful in some degree in addressing the underlying conditions that lead to crime, including lack of education, joblessness, homelessness, and urban blight.

In Ringerike, Norway a prison officer talks with an inmate in his cell.

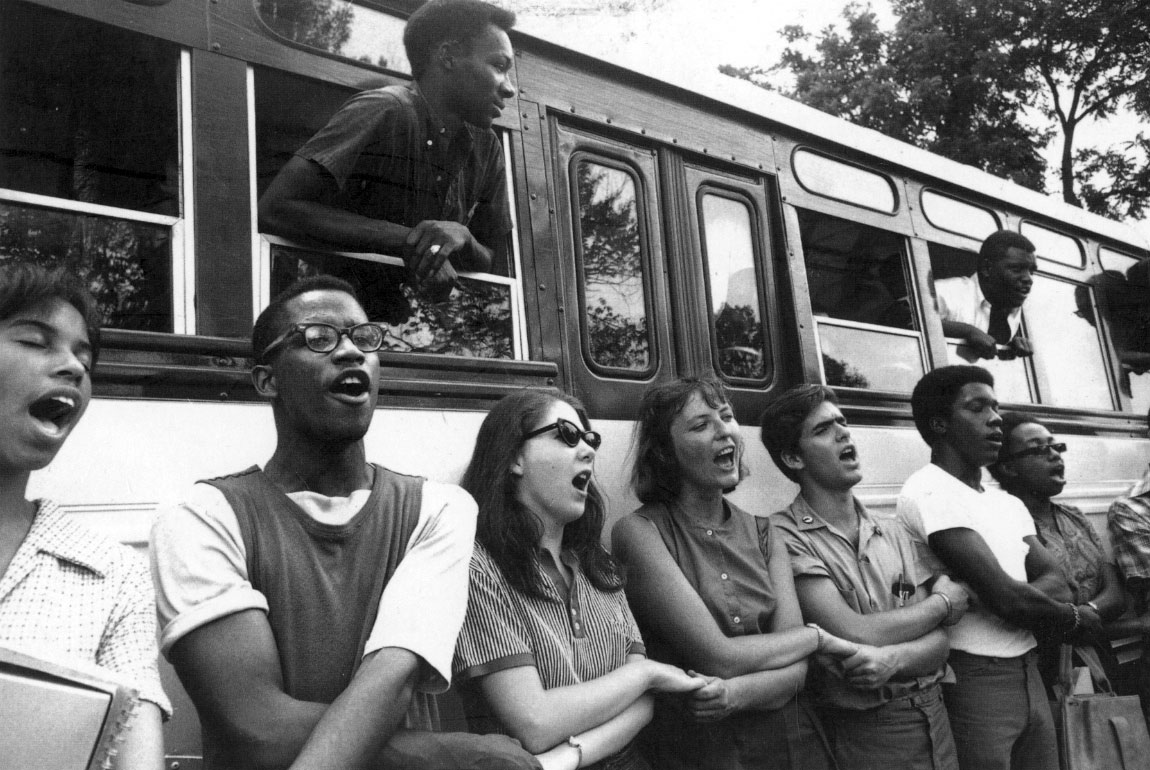

“If Martin Luther King Jr. is right that the arc of history is long, but it bends toward justice, a new movement will arise …” — Michelle Alexander

It is common knowledge today in the United States that mass incarceration is ineffective and cruel. Organizations working to radically reform the current system include the Equal Justice Initiative and the Vera Institute of Justice.

In the last chapter of her book The New Jim Crow,” Michelle Alexander suggests a path forward for us in the United States:

“Taking our cue from the courageous civil rights advocates who refused to defend themselves, marching unarmed past white mobs that threatened to kill them, we, too, must be the change we hope to create. If we want to do more than just end mass incarceration—if we want to put an end to the history of racial caste in America—we must lay down our racial bribes, join hands with people of all colors who are not content to wait for change to trickle down, and say to those who would stand in our way: Accept all of us or none.”

The Equal Justice Initiative believes that “ending mass incarceration is the civil rights issue of our time.” Combined with improved social, health, and legal aid services, these principles laid out in the Kampala Declaration on Prison Conditions in Africa are relevant:

- That the human rights of prisoners should be safeguarded at all times ….

- That prisoners should have living conditions which are compatible with human dignity.

- That conditions in which prisoners are held and the prison regulations should not aggravate the suffering already caused by the loss of liberty.

- That the detrimental effects of imprisonment should be minimized so that prisoners do not lose their self-respect and sense of personal responsibility.

- That prisoners should be given the opportunity to maintain and develop links with their families and the outside world.

- That prisoners should be given access to education and skills training in order to make it easier for them to reintegrate into society after their release.

Additional Reading

Bryan Stevenson, “Why American Prisons Owe Their Cruelty to Slavery”

Nicole-Hannah Jones, The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story

Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness

Laurent Dubois, Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution

C.L.R. James, Black Jacobins

David W. Blight, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom

Frederick Douglass, The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave

Anténor Firmin, On the Equality of Human Races

Carolyn Fluehr-Lobban, “Anténor Firmin and Haiti’s Contribution to Anthropology”

Laura Paddison, “How Norway Is Teaching America To Make Its Prisons More Humane”

If you would like assistance in getting reading access to any of the publications listed above, contact us here.

Video:

PBS, The Haitian Revolution

PBS, Haiti and the Dominican Republic: An Island Divided

Vox, Divided island: How Haiti and the Dominican Republic Became Two Worlds