Haiti and Germany

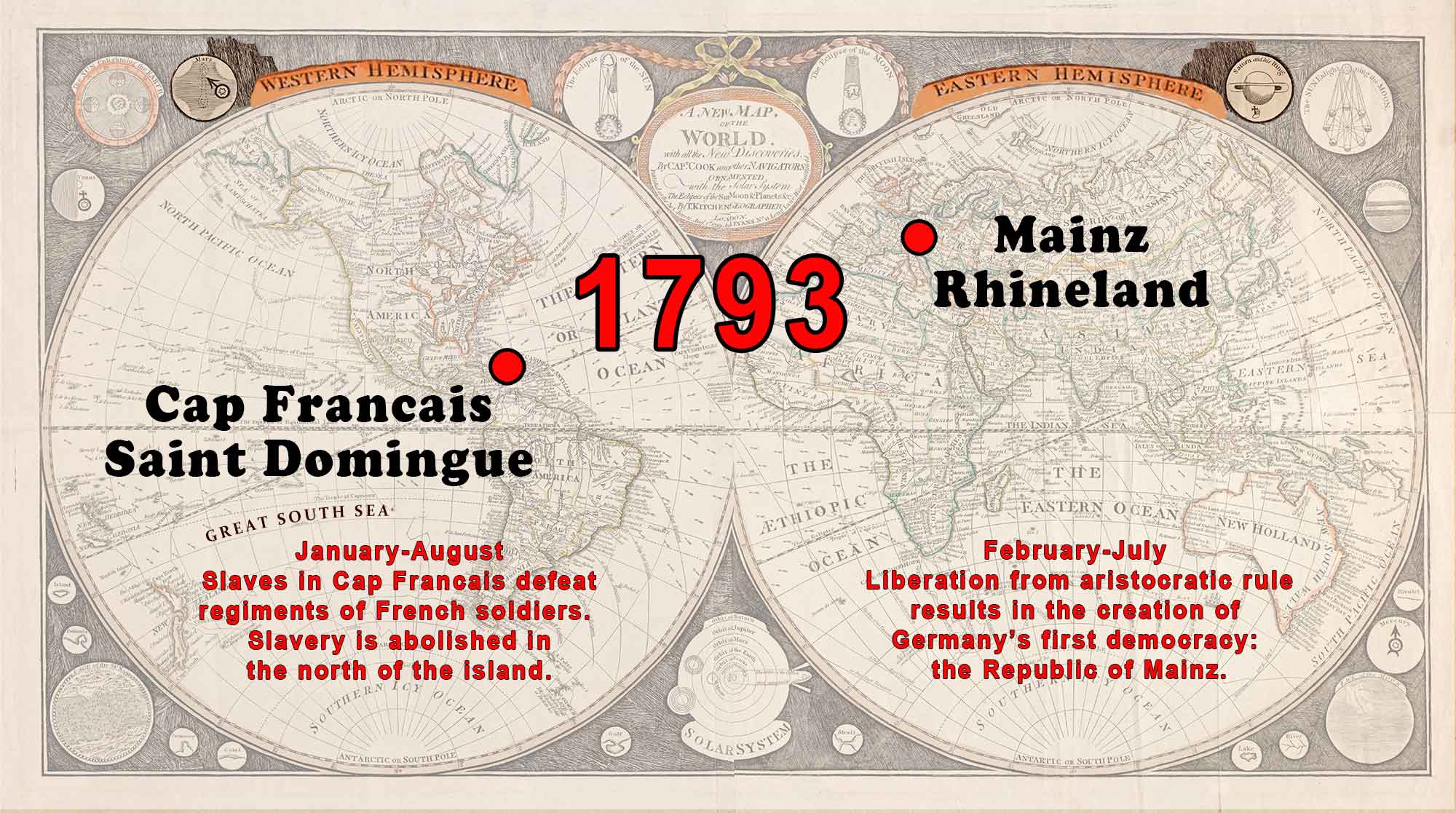

Although the Haitian uprising — the first ever to successfully abolish slavery — pursued a unique path to liberation, it did not occur in historical isolation. From the beginning, Haiti’s history has been interwoven with the experiences of other peoples and their revolutions, including the United States (achieved independence in 1776), France (revolution 1789-1792), and a region in what is now Germany: Mainz.

Mainz, located in Germany’s Rhineland, set up a democratic republic in 1793.

Georg Forster, a leader of the Mainz Republic, recognized the Haitian Revolution as an anti-colonial struggle with its own principles and individual character. Yet he also believed that all the liberation movements of his time were linked through shared values of freedom, equality, and human dignity. He closely followed the news reports about the slave insurrection in Saint Domingue, and he was not alone in doing so. In the late 18th century, Germany did not yet exist as a nation with colonial interests; hence there was less censorship of information about Saint Domingue and broader support for the island’s revolution than existed elsewhere in Europe. (When Germany did become a colonial power in the late 19th century, however, its policies were as exploitative and cruel as those of other European nations and the U.S..)

Those who fought against slavery in Saint Domingue were separated by an ocean — and of course much more — from Rhinelanders in Mainz seeking their freedom. What Forster responded to in both movements, though, was “ein anderer Begriff von Menscheit” (another concept of humanity) that he believed could inaugurate a better world.

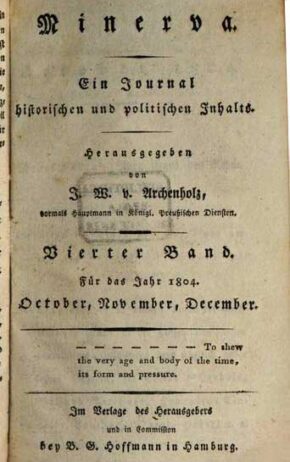

Georg Forster stayed up to date about the slave uprising in Haiti, as did Heinrich von Kleist, the author of the novella on which our play Betrayal is based. Like many German readers, they learned about events from eyewitness accounts that were published regularly in Minerva, a journal that was based in Hamburg. Announcing that “The eyes of the world are now on St. Domingo,” the journal regularly reported on the revolution from its inception in 1792 through the foundation of the state of Haiti in 1804, and among its readers were Goethe, Schiller, and the king of Prussia.

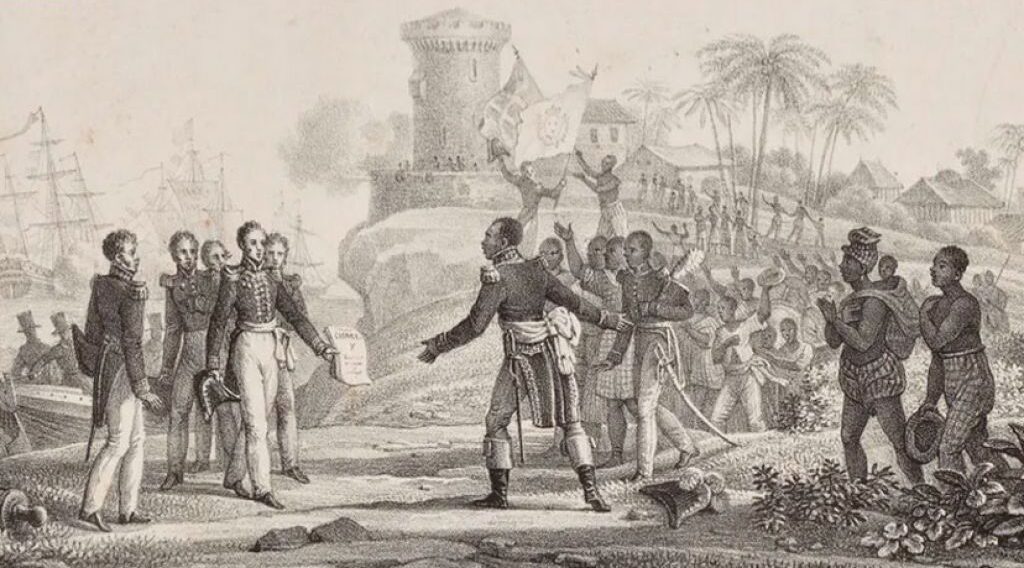

In the fall of 1792, a year after the slave revolt has begun, French commissar Sonthonax arrives in Cap Francais, with the mission of pacifying the island. But in the spring of 1793, a French naval officer, General Galbaud, decides to join white settlers in organizing a rebellion to take over the city. In June Sonthonax agrees to free enslaved people in the city, on the condition that they fight against Galbaud’s forces. They do so, Galbaud is defeated, and in August Sonthonax issues an emancipation proclamation (which he is holding) abolishing slavery in the northern province. (portrait from the Musée du peigne et de la plasturgie à Oyonnax)

In the fall of 1792, a year after the slave revolt has begun, French commissar Sonthonax arrives in Cap Francais, with the mission of pacifying the island. But in the spring of 1793, a French naval officer, General Galbaud, decides to join white settlers in organizing a rebellion to take over the city. In June Sonthonax agrees to free enslaved people in the city, on the condition that they fight against Galbaud’s forces. They do so, Galbaud is defeated, and in August Sonthonax issues an emancipation proclamation (which he is holding) abolishing slavery in the northern province. (portrait from the Musée du peigne et de la plasturgie à Oyonnax)

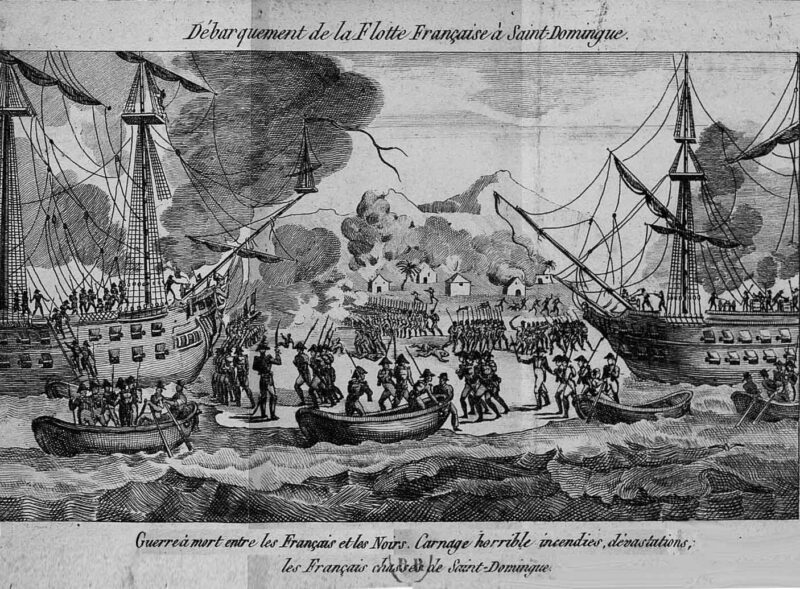

Galbaud’s defeat, though, does not put an end to slavery on the island. The slave revolt continues, and thousands of French soldiers are sent to Cap Francais to put it down. The caption above summarizes what takes place: War to the death between the French and the Blacks. Horrible carnage, fires, devastation, the French expelled from Saint Domingue.

October 1792. Mainz surrenders to French General Custine. Honoring the ideals of the French Revolution, he announces to the townspeople, “Your own, unconstrained will should decide your fate.” (Stadtarchiv Mainz)

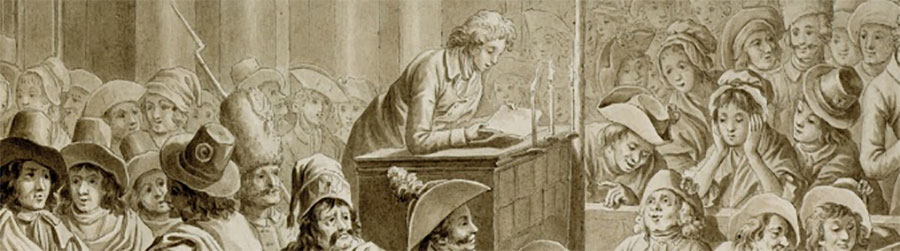

Celebrating their liberation, Mainz citizens of all walks of life dance around the “tree of freedom.” (artist unknown)

There were many Mainz residents, though, who did not support the creation of this new social order and who did not participate in its processes of democratic governance.

In August 1793 Black revolutionary Toussaint Louverture issues a proclamation: “Perhaps my name has made itself known to you. I have undertaken vengeance. I want Liberty and Equality to reign in Saint Domingue. I am working to make that happen. Unite yourselves to us, brothers, and fight with us for the same cause.” By the end of 1793, his forces have achieved military control of much of the island.

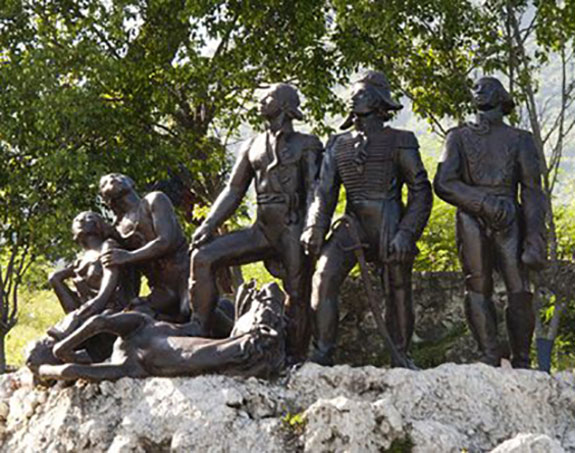

The final, decisive battle of the Haitian Revolution is fought on the outskirts of Cap Francais in 1803. Today, a monument, located near the site of the battle, acclaims the victory, but recognizes the terrible loss of life.

“Tonight at 6 o’clock a society of German friends of freedom and equality from all classes will meet in the large academy hall at the local castle and take a solemn oath to live free or die.” Residents of the Mainz region choose to create a republic with a parliament of elected representatives. (Stadtarchiv Mainz)

This new republic never achieved true independence, however. French administration of Mainz became increasingly authoritarian as the defeat of the Republic approached.

Georg Forster

Organizer of the Mainz Republic

Supported the Haitian Revolution

Naturalist, ethnologist, journalist

Caroline Schelling

Backer of the Mainz Republic

Imprisoned for her political views

Literary Critic

Advocate for women’s rights

Forster proposed that the European Enlightenment, which inspired 18th-century revolutions, did not originate in Europe: “Would reason have developed so readily among Northern peoples if Chaldea, India, and Egypt had not already taken steps in this direction? If alphabetic writing, along with arts and sciences, had not migrated from Africa and Asia to Greece … bringing about an Age of Enlightenment?”

“I have seen 160 prisoners … plundered, beaten to within an inch of their lives … what strength is left in these arms now rises up against what is happening here.”

With the help of her brother, Schelling was able to secure her release from prison and to escape from Mainz when the aristocratic order returned and sought to punish those who had supported the revolution.

Although French troops have been decisively defeated in the mountains, fields, and townships of Haiti, France is not about to give up its control of the island. As a condition of Haiti’s independence, the king of France decrees that Haiti will have to pay 150 million francs within five years to compensate for slave owners’ lost revenue.

In 1824 Charles X sends a French envoy to deliver his demand for compensation to Haiti’s President Boyer. To compel Haitian acceptance, the envoy is accompanied by 14 warships bearing more than 500 cannons.

Additional Reading

When a liberation movement succeeds in overthrowing an oppressive social order and forming a new republic – as happened in Haiti and Mainz in the late 18th century – it typically faces daunting new obstacles. Quite often, the very forces that have been overthrown seek to defeat the revolution and return to power. As well, divisions internal to the revolution — fighting that goes on between followers of one leader and followers of another, for example — may trample on the values of freedom and equality that motivated the revolutionary actors in the beginning.

Truthful accounts of these revolutions don’t hide this complexity. To look more deeply into the history of the Haitian uprising, or the one in Mainz, the following readings are recommended:

Haiti

Laurent Dubois, Haiti

Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Haiti: State Against Nation

Laurent Dubois, Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution

Charles Forsdick and Christian Hogsbjerg, Toussaint Louverture

C.L.R. James, Black Jacobins

Battle of Vertières

Mainz

Franz Dumont, “Nine Theses on the Republic of Mainz”

Jurgen Goldstein, Georg Forster: Voyager, Naturalist, Revolutionary

Impassioned defenders of the Mainz Republic — its values, methods, and achievements — are historians Heinrich Scheel and Walter Grab. Accounts more critical of the Republic are provided by historians Franz Dumont and T.C.W. Blanning.

If you would like assistance in getting reading access to any of the publications listed above, contact us here.

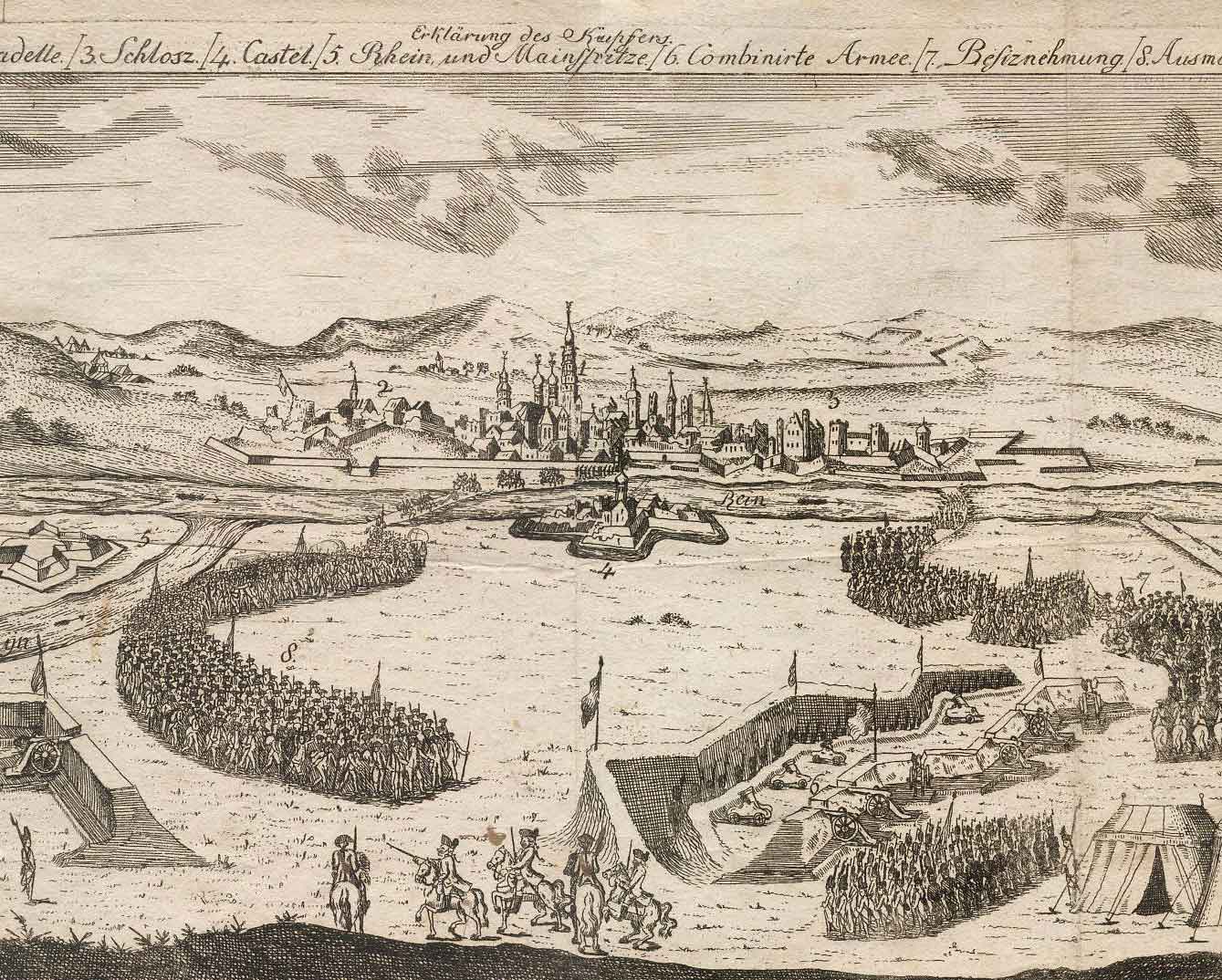

April-July 1793. Prussian and Austrian troops lay siege to Mainz.

One reason that Mainz is unable to transition the revolution in 1792 into a stable democratic republic is that Mainz is besieged by the armed forces of Prussia and Austria.

Late July 1793. Mainz is on fire from the shelling. The Republic surrenders. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Germany’s most famous man of letters, lamented that “Ashes and ruins were all that was left of what had taken centuries to build.” (painting by Georg Schneider)

More on Toussaint Louverture

Engraving source unknown

Born a slave, Toussaint Louverture became a skilled battlefield general, negotiator, and law-maker who led the Haitian uprising against slavery. His military and political leadership helped transform the insurrection into a revolution. He is known today as the “Father of Haiti.”

Navigating the complex politics of competing colonial powers, he successfully repelled the armies of France, Spain and England. In 1801 he wrote the “Saint Domingue Constitution,” which declares that “servitude has been forever abolished.” Near the end of the revolutionary war, Louverture was invited to meet with a French general, but was arrested upon his arrival. He was deported to France, imprisoned there, and died in 1803.

More on Georg Forster

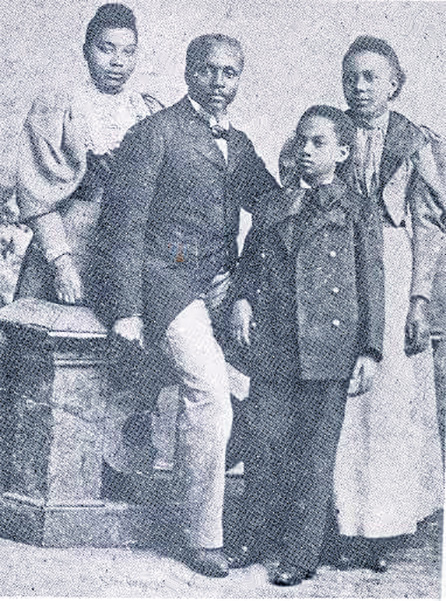

Forster is shown here at the age of 18, in the company of his father during their 3-year voyage around the world with Captain Cook. Georg Forster supported the slave uprising in Haiti, and predicted resistance elsewhere in the world against colonial regimes. In Germany he brought to the task of leading the Mainz Republic a lifetime of experience as an explorer and scientist. He was an anthropologist as well as an observer of flora and fauna. He learned the languages spoken on the Polynesian islands he visited, and tried to put aside Christian-Western prejudice in his interactions with native inhabitants. He criticized the idea of the “noble savage” and the European sorting of people into “races.” Human affairs, Forster believed, are shaped by culture and climate, not determined by biology. Painting by John Francis Rigaud

Forster is shown here at the age of 18, in the company of his father during their 3-year voyage around the world with Captain Cook. Georg Forster supported the slave uprising in Haiti, and predicted resistance elsewhere in the world against colonial regimes. In Germany he brought to the task of leading the Mainz Republic a lifetime of experience as an explorer and scientist. He was an anthropologist as well as an observer of flora and fauna. He learned the languages spoken on the Polynesian islands he visited, and tried to put aside Christian-Western prejudice in his interactions with native inhabitants. He criticized the idea of the “noble savage” and the European sorting of people into “races.” Human affairs, Forster believed, are shaped by culture and climate, not determined by biology. Painting by John Francis Rigaud

The Anti-Colonial Legacy of Georg Forster

Germany became a colonial power only after it established a national identity in 1871, much later than other European countries and the United States. When it did become a nation, Germany’s colonial practices were no more enlightened than those of other colonial empires. Before that, though, there was in German-speaking Central Europe considerable opposition to colonial rule and opposition to slavery.

Georg Forster was among those who spoke out strongly against colonial rule, and who supported the Haitian Revolution specifically. Thanks to his widely read books about his world-wide travels, he became well-known as an acute critic of colonial rule. In Reise um die Welt (A Voyage Round the World, 1777), which was translated into many languages, he described the harmful impact of European empire on native peoples:

“If it were ever possible for Europeans to have humanity enough to acknowledge the indigenous tribes of the South Sea as their brethren, we might have settlements which would not be defiled with the blood of innocent nations.”

To be sure, Forster’s writings are inseparable from Europe’s imperial project. At the same time, though, Forster’s respect for non-European ways of life was sharply at odds with British and French colonial discourses. His criticism of slavery, for instance, agreed with abolitionist movements in Europe and the United States. Forster also influenced those who knew him personally, including Therese Huber, to whom he was married for a time, and his student Alexander Humboldt.

Mentored by Forster, Alexander von Humboldt became the 19th century’s most eminent world traveler, anthropologist and environmentalist.

Alexander von Humboldt, like Forster before him, experienced and valued the earth’s biological diversity. He too was opposed to colonial empire and to slavery. More than Forster, though, Humboldt focused his attention on Latin America, including the Caribbean.

Everywhere he went, Humboldt observed the intimate relationships between climate, geography, and human habitation. He could understand, for example, that in a Caribbean island environment, a native insurrection might succeed in defeating a well-equipped foreign army.

It was Haiti’s mountainous jungle that enabled the world’s first successful guerilla campaign against a colonial empire. French troops were confused and ill-prepared to deal with resistance of this kind.

The island’s environment contributed to the success of the revolution in other ways too. Malaria, smallpox, and yellow fever, which were species that flourished in Haiti’s forests, devastated the invading French troops. Although those who were enslaved died from these diseases too, they had gained some immunity because of their lifelong exposure.

Humboldt dispelled many of the myths that Europeans constructed about peoples of the “New World, including the assumption that their native languages were impoverished compared to those spoken on the European continent. “The language of the Caribs,” he observed, “is at the same time rich, beautiful, energetic, and polite. It is not at all lacking in expressions for abstract ideas; one can speak of posterity, eternity, existence, etc.”

Therese Huber was an editor, translator, and prolific author of stories and novels.

Therese Huber and her husband Georg Forster lived in Mainz at the time of the French Revolution and the creation of the Mainz Republic. She supported these social upheavals, recognizing them as justified struggles for human liberation. But she saw the short-comings in both revolutions. She parted ways physically and in some degree politically with Forster, and in her fiction she dealt with the difficulty of building a post-revolutionary life.

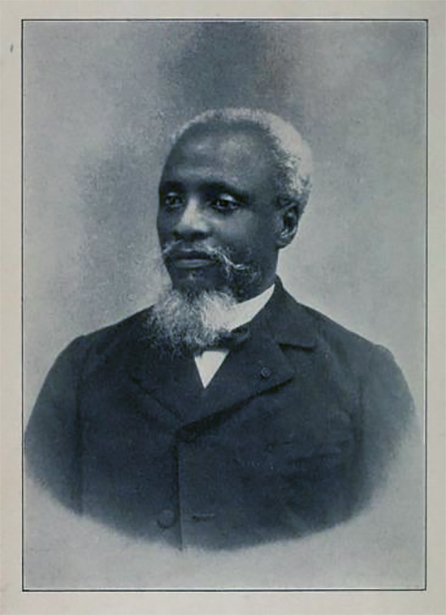

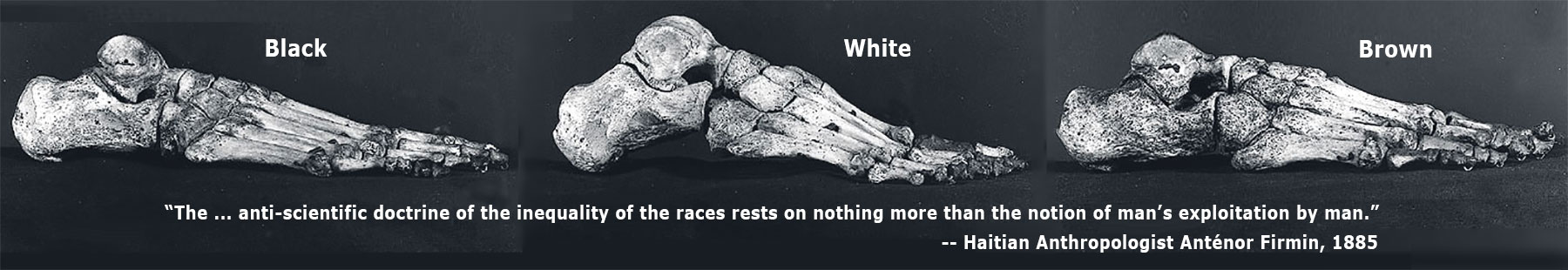

Haitian Anthropologist Anténor Firmin (1850-1911)

Alexander Humboldt, who was one of the founders of the field of anthropology in the first half of the 19th century, had very effectively debunked the idea that racial difference could justify human domination. Anténor Firmin, writing in the second half of the century, respected Humboldt’s contributions, but believed that a science-based anthropology would have to depart more sharply from — and also explain — its own colonial origins.

The publication of Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species in 1859 had given new life to racist ideologies, including the misuse of Darwin’s theory of evolution to re-affirm stereotypes about people of color. Firmin found that many of his colleagues accepted these stereotypes and embraced a narrow physical anthropology whose “preconceived systems … make natural facts conform to certain theories.’’

In his 600 page study entitled On the Equality of the Human Races, Firmin painstakingly considered the evidence bearing on issues of racial difference, reaching the conclusion that “human beings everywhere are endowed with the same qualities and defects, without distinctions based on color or anatomical shape…. They are all capable of rising to the most noble virtues, of reaching the highest intellectual development; they are equally capable of falling into a state of total degeneration…. It is a fact that an invisible chain links all the members of humanity in a common circle.”

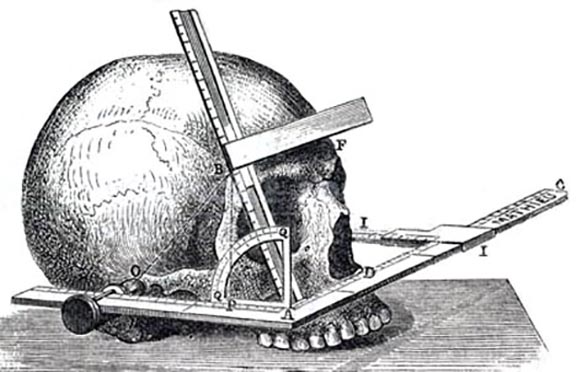

Craniometry was an empirical tool commonly deployed in late 19th-century anthropology. In his book Mismeasure of Man (1981) evolutionary biologist Stephen J. Gould extended Firmin’s critique of cranial pseudo-science.

Paul Broca (1824-1880), a French professor of medical surgery, founded the Anthropological Society of Paris in 1859. He believed that the dimensions of the skull, along with physical properties such as skin color and hair texture, could be used to rank humans in terms of their intellectual and social capacities. Firmin showed in mathematical detail that Broca’s data and inferences based on that data were faulty, concluding with a caustic take-down of such inquiry:

So we would look in vain for a craniometric method for identifying that mysterious characteristic by which anthropoplogists might recognize the differences which signify a natural hierarchy among the various groups of the human species. Turn it this way or that way, the skull remains mute, with its sepulchral [tomb-like] look …. Undoubtedly, the skull did at one time shelter thought, intelligence, in a word, everything that constitutes true superiority. But just as a poor man’s cabin keeps no visible trace of the passage of a prince who may have paid it a brief visit, a skull keeps no imprint of the thoughts it may once have sheltered.”

Additional Reading

Jürgen Goldstein, Georg Forster: Voyager, Naturalist, Revolutionary

Andrea Wulf, The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt’s New World

Russell Berman, Enlightenment or Empire: Colonial Discourse in German Culture

Chunjie Zhang, “Georg Forster in Tahiti: Enlightenment, Sentiment and the Intrusion of the South Seas”

Aaron Sachs, “‘The Ultimate ‘Other’: Post-Colonialism and Alexander Von Humboldt’s Ecological Relationship with Nature”

Susanne Zantop, “Colonial Fantasies: Conquest, Family, and Nation in Precolonial Germany, 1770-1870”

Carolyn Fluehr-Lobban, “Anténor Firmin: Haitian Pioneer of Anthropology”

If you would like assistance in getting reading access to any of the publications listed above, contact us here.