Art and Revolution

The insurrection against slavery on the Caribbean island of Saint Domingue (Haiti) alarmed slave holders throughout the Americas — they understood that those whom they held in bondage might rebel too, and equally violently. Indeed movements to abolish slavery were inspired by what was happening in Saint Domingue. The insurrection also unleashed a torrent of literary creativity.

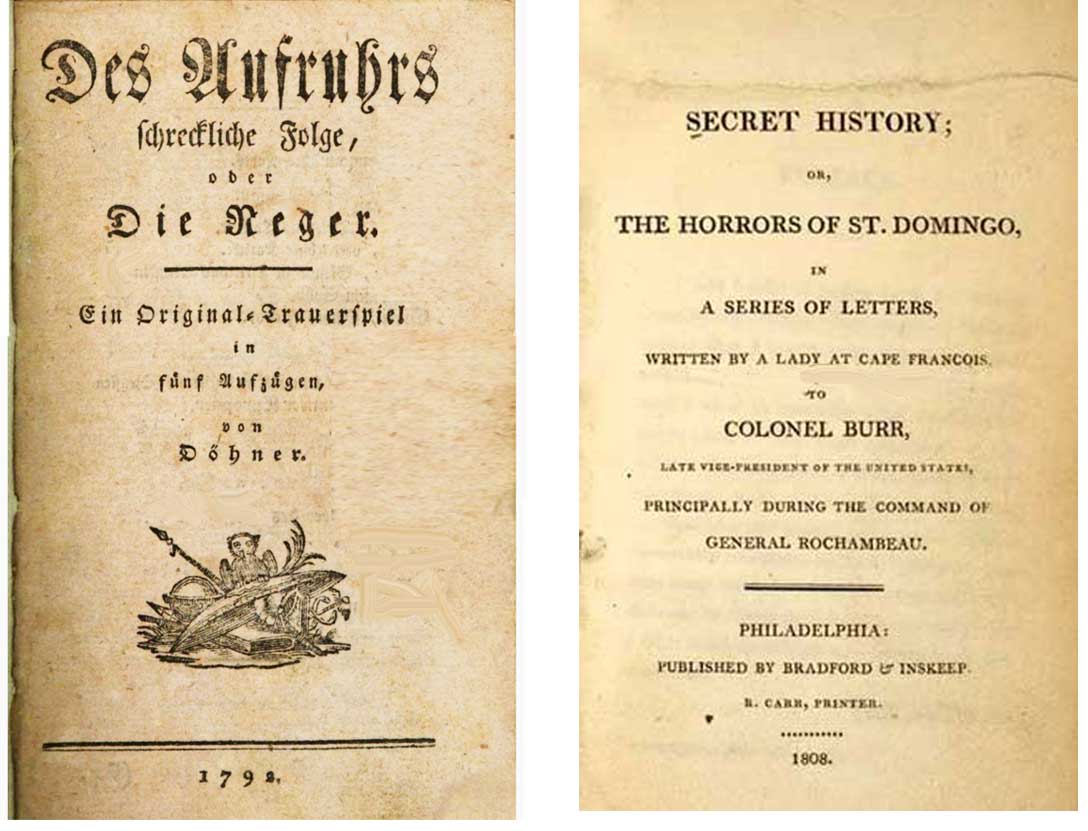

Already during the first years of the uprising, German-speaking writers were publishing novels and dramas about it, including Friedrich Döhner’s The Terrible Consequences of the Rebellion in 1792 and Johann Gottfried Herder’s Negro Idylls in 1796.

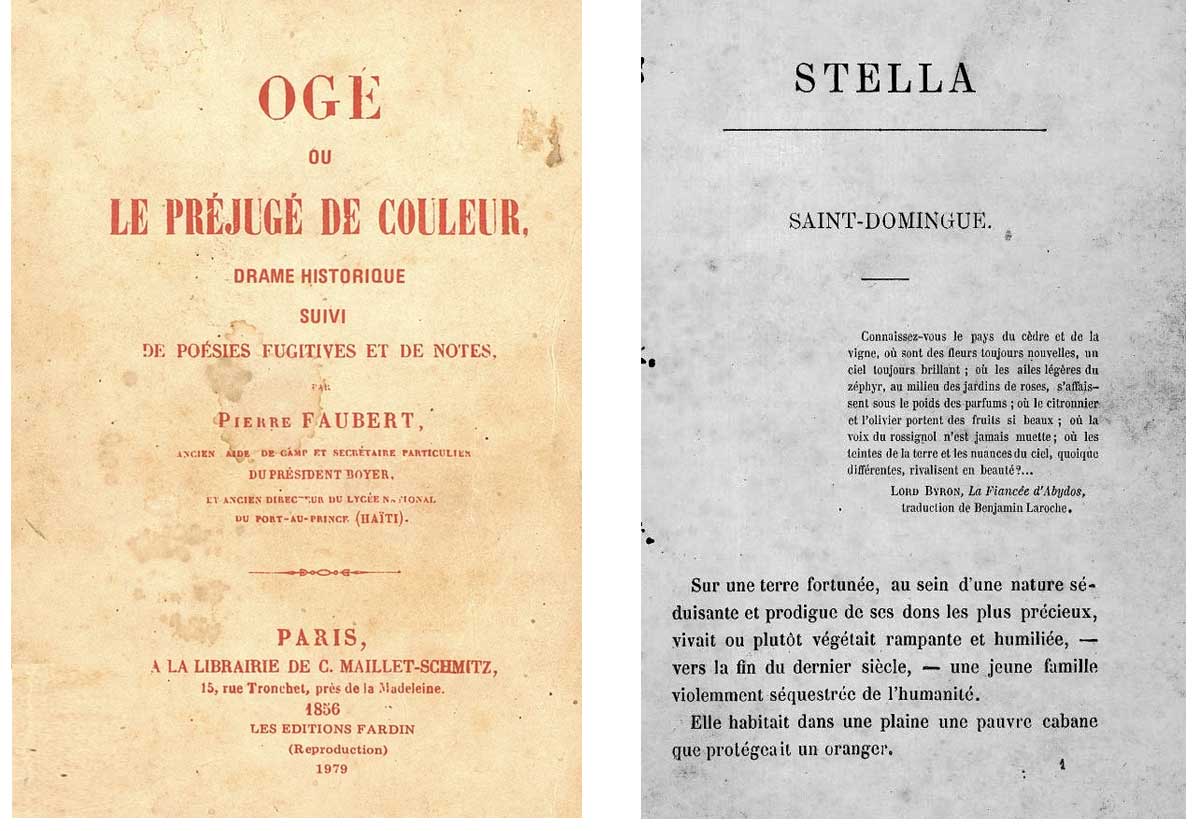

In the United States in 1808, Leonora Sansay wrote a “Secret History” that portrayed two sisters living through the final defeat of the French military in Saint Domingue. In France and England too, writers were motivated by the Haitian Revolution to re-imagine relationships of race, class, and gender. Two works written in the 19th century by Haitians were Faubert’s play Ogé or the Prejudice of Color in 1856 and Bergeaud’s novel, Stella in 1859.

Our concentration here, though, will be 20th-century artists who have been inspired by the Haitian Revolution. Among them in the United States were writers and painters of the Harlem Renaissance during the early decades of the 20th century, including the author, anthropologist, and filmmaker Zora Neale Hurston.

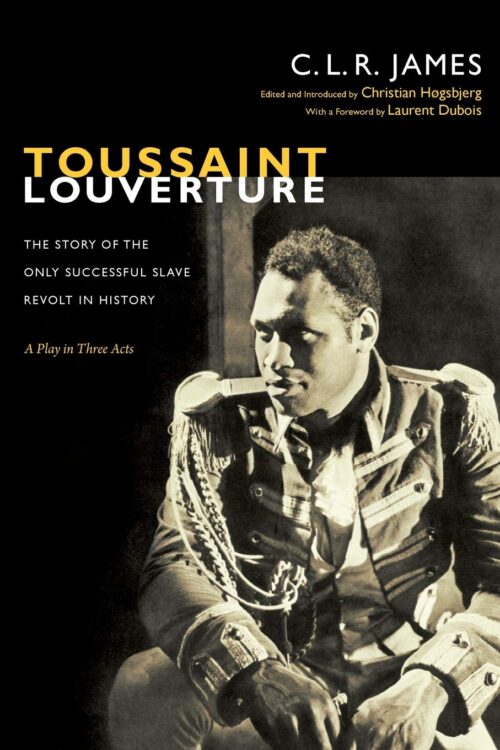

Following in their footsteps, the painter Jacob Lawrence gave visual representation to the revolution. Historian and political organizer C.L.R. James freshly analyzed this first successful slave revolt in the modern world in Black Jacobins (1938), an account that remains influential today. James also wrote a play, Toussaint Louverture, that was performed in London in 1936, with world-famous singer and actor Paul Robeson playing the title role.

Contemporary with Lawrence and James, Haitian painter Hector Hyppolite and poet Jean-Fernand Brierre were influenced by the Haitian Revolution too, each of them remembering and representing the fight for freedom in unique ways that we’ll review below.

Inseparable from the revolution from the very beginning has been the Vodou religious tradition, which enters into the work of Hyppolite, Philippe Dodard, and many other Haitian artists. Discussed below is the contribution made by one of the goddesses in that tradition, Erzulie Freda/Danto, to our play Betrayal in Haiti.

We’ll conclude this web page with a look at the life and work of the German author, Heinrich von Kleist, who in 1811 wrote the novella that is the basis for the play.

Zora Neale Hurston

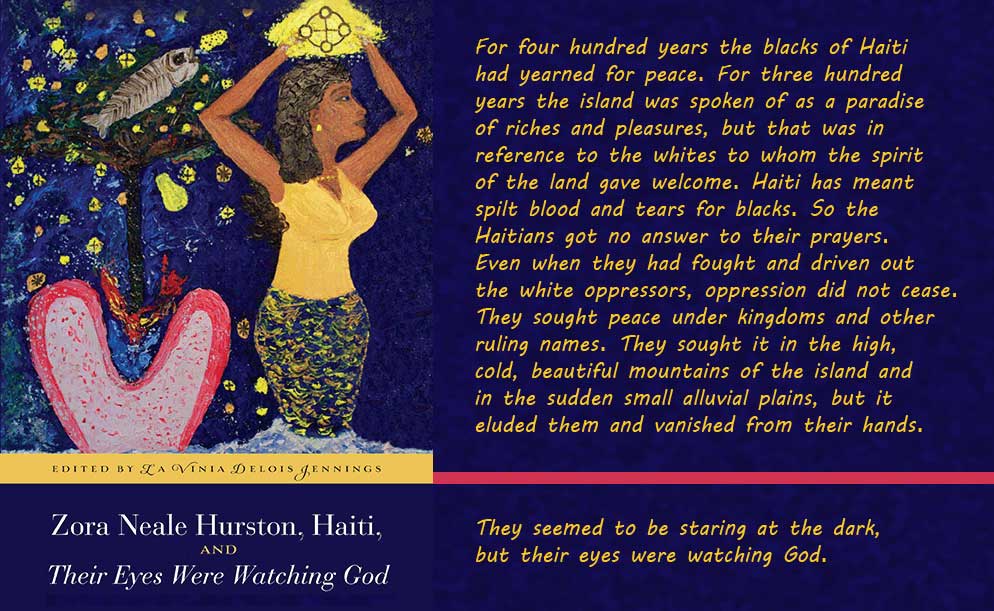

Zora Neale Hurston (1891-1960) wrote her famous novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God, in Haiti, where she had gone as an anthropologist to study the island’s folk culture. Her research provided not only data for her ethnography but also a subtext for her fiction.

Hurston’s vision was wide, encompassing the universal values of the Haitian Revolution — the commitment to freedom, equality, and justice for all — while also recognizing its significance as a Black insurgency fighting for separation and liberation from the world’s colonial powers.

Jacob Lawrence

Harlem Renaissance artist Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000) painted a series on The Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture. The original works were created between 1936 and 1938, a time when Black people in the United States as well as in Haiti (which was occupied by the U.S. Marines from 1915 to 1934) continued to be cast in stereotypes of ignorance and ineptitude. Lawrence brought to bear a different perspective, in keeping with the account given by Trinidadian-British historian C. L. R. James (1901-1989) in The Black Jacobins (1938): “The transformation of slaves, trembling in hundreds before a single white man, into a people able to organize themselves and defeat the most powerful European nations of their day, is one of the great epics of revolutionary struggle and achievement.”

Lawrence conveys in his art the collective intelligence and commitment of the enslaved rebels that enabled them to outmaneuver and defeat the French army.

Toussaint L’Ouverture at Ennery (Jacob Lawrence)

Strategy (Jacob Lawrence)

Philippe Dodard

Philippe Dodard is a contemporary Haitian painter, illustrator, and sculptor who makes use of traditional Haitian and African symbols and motifs in his art. Although his paintings are rarely directly political, they give expression to memory and hope and love of life in its countless forms.

Magic Encounter

Salt Fish

The Rising

Mother and Daughter

Hector Hyppolite

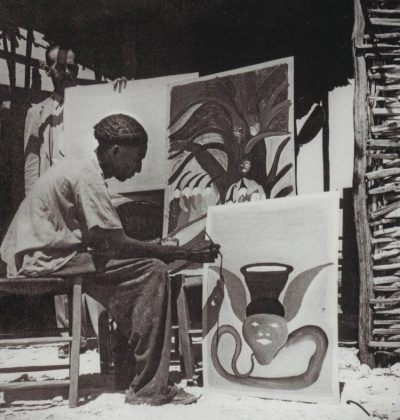

A self-taught Haitian artist, Hector Hyppolite (1894–1948) began by painting illustrations on furniture and doors with brushes made of chicken feathers. His occupations were many — shoe maker, house painter, and vodou priest — before he took up fine art painting. The hundreds of works he created in the last three years of his life made him a legend in Haiti and brought him international recognition as well.

Erzulie

The French writer Andre Breton welcomed Hyppolite into the surrealist movement and purchased five of Hyppolite’s paintings when he visited Haiti in 1945.

To the left, the painting Papa Zaka Papa Ogou represents two Vodou spirits, transformed into revolutionary leaders who fight Haiti’s demons.

Hector Hyppolite at work

As a young man, Brierre administered and taught in rural schools near to Jeremie. He then became a diplomat for his country and spent time in France, Argentina, and the United States. In 1932 Brierre expressed his opposition to the ruling regime in Haiti by founding the political newspaper “La Bataille.” Because of his criticism of Haiti’s government and of the American occupation (1915-1934) of the island, he was imprisoned for two years in the national penitentiary. When Duvalier came to power in Haiti, Brierre remained in the opposition. He was once again imprisoned, this time for nine months in 1962. Upon his release he went into exile in Senegal, returning to Haiti 25 years later when the Duvalier regime had been overthrown. Throughout his adult life he was enormously prolific as an author of essays and poetry.

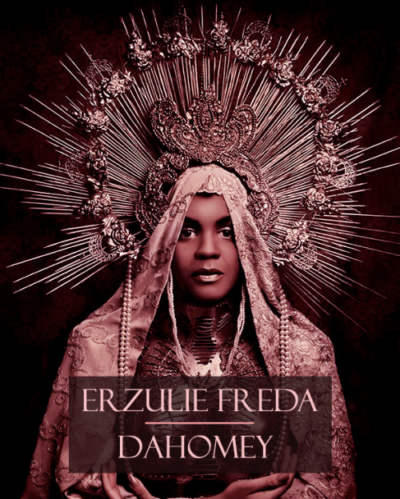

Erzulie Freda/Erzulie Danto

Haitian art often draws upon the island’s Vodou tradition, belonging to a people whose lives during centuries of slavery were tortured and strained to the breaking point. And when at last the revolution succeeded, much of its promise of liberation was shattered by on-going exploitation at the hands of foreign powers and the nation’s own domestic leadership.

Vodou, which has its roots in West Africa, provides a language of symbols and images that informs some Haitian art — that of Hector Hyppolite, for instance — or created by writers of the Black diaspora like Zora Neale Hurston.

In the play Betrayal in Haiti, a plantation house that Babekan and other former slaves have taken over is inhabited by spirit voices. Babekan’s closest conversational partner is Erzulie, a Vodou goddess who is sometimes loving, generous, and fair-minded, but who also has a destructive side that displays selfishness, infidelity, and malice. In the form of Erzulie Freda she loves and protects, provides shelter and bestows blessings. But Erzulie is also “Danto,” meaning “does wrong” in Creole. Erzulie Danto can ruin the life of someone she takes a disliking to. She will kill to protect someone she loves. She sides with the Black revolt in Saint Domingue, passionately protecting “her children” from their oppressors. She gives support especially to the slave women of the island, humiliated and violated beyond imagining.

Erzulie’s double nature recalls the pre-Christian goddess Freia of Norse mythology, who both protects and exacts vengeance, and the Furies of the Ancient Greeks: three goddesses whose mission is justice, however cruel.

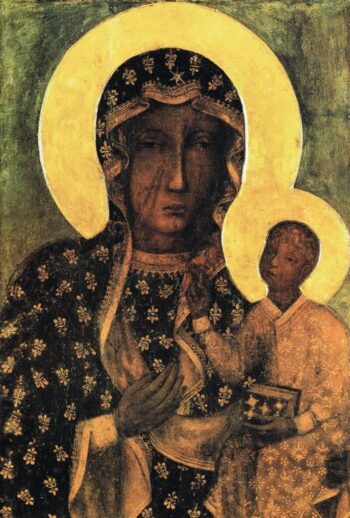

Haitian art draws as well on Christian tradition in representing Erzulie as the Black Madonna — “Mater Dolorosa,” the mother of sorrows. The Black Madonna may have been first introduced to the island by Polish soldiers recruited to fight alongside the French, but in the guise of Erzulie she changes sides and fights for the Blacks instead. (Some of the Polish soldiers also changed sides and fought alongside the former slaves. They were called “the White Negroes of Europe” by rebel leader Jean-Jacques Dessalines.)

The two scars on the cheek of Erzulie Dantor are permanent reminders of the battles she has waged on behalf of her children.

BABEKAN: Three months ago, on a night when the stars were covered over and no bird was singing, lightning exploded in the forest, and we all understood. Erzulie Danto, queen of the moon, avenges, avenges until they are gone. Every. Last. One.

Icon of the Black Madonna at the Jasna Góra Monastery in Częstochowa, Poland.

Heinrich von Kleist

In 1811, seven years after Haiti won its independence, Heinrich Wilhelm von Kleist (1777-1811) wrote the novella Betrayal in Haiti on which our play is based. Kleist was a poet, story writer, dramatist, and journalist. He never visited Haiti, but learned about the slave uprising through published eye-witness accounts.

Although Kleist fell short of understanding the Haitian Revolution on its own terms, he could sympathize with the aim of liberation. Kleist’s Prussia, like Haiti, suffered from domination by the Napoleonic Empire. Kleist himself was imprisoned in 1807 when he was traveling in France and accused of espionage. He was held in the same location, Fort de Joux (a castle turned into a state prison), where four years earlier Toussaint Louverture, famous leader of the Haitian Revolution, had been incarcerated. Although Toussaint had quit the battlefield following an armistice, and had retired from the military, the French General LeClerc had him arrested in June 1802 and shipped to France. In a prison cell, suffering from the extreme cold and other unbearable conditions, he died ten months later.

Kleist’s treatment of race in his novella is inconsistent, re-affirming stereotypes about human differences while at the same time calling into question European colonial assumptions about the conduct and capacities of people of color. On the one hand, Kleist misunderstands the aims and ideals that motivated the revolutionaries: he conceives the Haitian Revolution (like the terrorist phase of the French Revolution) as defined and driven by vindictive rage on the part of the island’s people of color. On the other hand, Kleist recognizes the false assumptions built into racial categories, and he writes with some insight into the dilemmas that arise in situations of violent confrontation between colonial subjects and their masters.

There is a contradiction that runs through Kleist’s story: the narrator in the story observes the revolt against slavery in Haiti through the lens of a naive white European perspective. But this descriptive framework is belied by the events themselves and by the characters’ responses to those events. In our adaptation, we work with what the characters in the novella say and do, sometimes putting aside the commentary offered by the narrator.

Kleist, having written the novella from which this play is adapted and feeling mentally exhausted and financially worried, decided he would live no longer. He and his dear friend Henriette Vogel, despondent about her cancer diagnosis, penned farewell letters in Berlin and then, on November 21, 1811, they traveled to Wannsee, nearby. There they walked to the shore of a small lake and carried out their suicide pact. Kleist shot his companion and then himself. Because of the way they ended their lives, they were not eligible for church burial and were interred where they died.

Fort de Joux in France, where Toussaint Louverture was imprisoned in 1803 and Kleist in 1807.